Luddy School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering professors Selma Šabanović and David Crandall remember the moment it seemed to all come together -- science, technology, and humanity -- in one emotional conversation during the United Nations' AI for Good Global Summit in Geneva, Switzerland.

Only one participant was human.

A young man with special needs was talking with the Luddy School’s I.R.I.S. robot, which stands for Interactive Robot for Ikigai Support. The AI-directed I.R.I.S. engages in conversations and offers suggestions to support people in finding purpose and meaning in their lives.

The young man told the robot he wanted to be a policeman. I.R.I.S asked why? The young man said because he liked to help and save people. I.R.I.S. responded that maybe he could consider volunteering at a local pet shelter. The conversation went on for more than 10 minutes.

“His parents asked if they could buy our robot because they rarely saw him engage in a conversation like that,” said Crandall, Luddy Professor of Computer Science and director of Luddy Artificial Intelligence Center. “He might not have been comfortable talking with another person, but he was engaged with the robot.”

Šabanović, Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and Professor of Informatics, added: “I.R.I.S. is supposed to learn what a person cares about through conversation. Then it points them to other activities they might not have thought about, but that are related to things they find meaningful.”

When I.R.I.S. said silly things, which robots sometimes do, the young man smiled and laughed.

“It was actually quite moving,” Crandall said. “I was almost fighting back tears because he was enjoying it so much.”

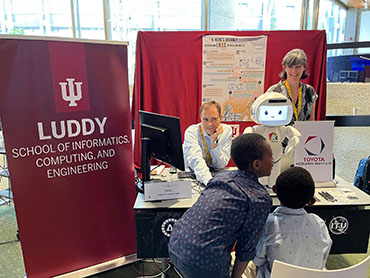

This was one of dozens of interactions that people had with I.R.I.S. during the July 6-7 event at the United Nations, which had invited Šabanović and Crandall to showcase their research on an international stage. The event drew more than 4,000 in-person participants from 183 countries. Many were world political and business leaders.

“It was really exciting to have a chance to talk to so many people about our work,” said Long-Jing Hsu, Ph.D. student in informatics who attended the event as part of the IU team. Her research is in human-robot interaction. “It’s not very often that you get to present and demo your work to such a wide variety of people.”

*****

I.R.I.S. is a collaboration between IU and Toyota Research Institute. Faculty and students from IU and TRI researchers designed and built I.R.I.S as an AI-controlled home robot prototype that supports and improves the sense of meaning and purpose in life (called ikigai in Japan) for older adults.

“This project involves working closely with older adults in the U.S. and Japan to design a robot that can learn about and help them maintain and expand their purpose in life,” Šabanović said. “How does the robot do that? What are the activities it can do with older adults? What are its behaviors, gestures, modes of speech, expressions. How do older adults want to interact with the robot over the course of a day, a week, a month? That’s what we’re trying to figure out.”

For the past two years, the IU team has worked with older adults from Jill’s House, a Bloomington memory care facility, to test the robot and get feedback from adults and staff. They also hold monthly robot design meetings with older adults from the local community.

“We want to see how these robots might be helpful for older adults generally and those with dementia specifically,” Šabanović said.

Šabanović said there’s a gap between the Hollywood-style vision of robots helping people everywhere and the reality of what robots can do and what people actually want them to do.

“When we talk to potential users, they often say, robots are so cool, but I don’t want one,” she said. “Where is that gap from? Robotics research and development needs to integrate users more actively into the design process so that their perspective can help guide the new technologies that are being created. That’s one of the things we’ve been doing with our projects.

At the UN summit, the 2.5-foot-tall I.R.I.S robot with a smiling face and earnest dark eyes -- one of more than 50 participating robots – talked to people in an almost childlike voice.

“There were several moments when people were surprised by the level of conversations they had with robots,” Šabanović said. “The robot asked them to show it a picture of something that was important to them from their cell phone, and it would recognize what was in the photo and ask questions and lead an open-ended dialogue based on that.”

Building I.R.I.S. involves not only solving technical challenges, but also understanding how to make people feel comfortable with a robot. For example, how the robot’s voice sounds can cause people to have different views of the robot’s intelligence, seriousness and trustworthiness.

“These factors vary from culture to culture,” Crandall says. “Selma and Long-Jing and their team did a cross-cultural study in the U.S. and Japan to study that.”

Crandall said that’s an example of why interdisciplinary collaborations are so important in AI research.

“A computer scientist like me use the first voice I found to download,” Crandall said, “whereas experts in human-robot interaction like Selma and her students know that voice is a super-important detail. You need to get it right or people won’t care or interact with the robot.”

In addition to presenting I.R.I.S., Šabanović and Crandall also presented a talk titled, “Developing robots to assist children and older adults,” along with Randy Gomez, chief scientist for Japan’s Honda Research Institute.

****

The invitation to present at the summit, with its diverse audience of politicians, professors, students and interested visitors, was a unique opportunity to enhance the Luddy School’s world-wide visibility.

“I gave people pitches about what makes us special,” Crandall said. “I hope we’ll get some extra undergraduate and graduate student applications from this.”

Crandall and Šabanović talked with United Nations’ Institute for Training and Research officials about how IU could help design and build education modules for their administrators and policymakers.

“The Luddy School works to connect technological expertise and innovation with societal impact,” Šabanović said. “It’s good for us to talk to these governmental, non-academic and non-industry partners.

Crandall said that many presenters at the summit were from companies trying to sell products. In contrast, IU works to serve the public good through its innovative research and educational opportunities.

“We provided a perspective that I hope was helpful to policymakers,” he said.

“We had a chance to cut through the hype of AI research, and talk about how to get to the real promise of these emerging technologies and put the resources and work behind efforts that could be societally beneficial, Šabanović said.

She said it was important to take their projects to a place outside of the academic realm and get feedback, gage interest and understand the questions and concerns of policymakers, people from governmental institutions and those from startups and tech companies.

“It was interesting to hear how they talk about AI and emerging technologies and what they pay attention to,” Šabanović said. “Having that broader audience to bounce our ideas off of was invaluable.”

That included addressing AI’s potential benefits and dangers. The UN could play a major regulatory role to help ensure safety.

“One of the things we talked about was how to engage with the UN to set standards and policy,” Šabanović said. “We need to figure out how technological development can be guided to ensure broader societal benefit. Trying to regulate something after it’s been created and sent out into the world is like trying to put cats back into the bag after you let them out.

“We need to work together to figure out what should be the limits, and what are the capabilities and potential consequences.”

Added Crandall: “This meeting was the perfect place for us to be. Both the Luddy School and the Luddy AI Center are very interdisciplinary and looking at the opportunities and challenges of AI from many viewpoints.”

UN and government officials were receptive, Šabanović added.

“It resonated with them. I hope we can make more such connections in the future. We did get an invite to attend next year.”